Quick Reads

People often seek pleasure from consumption of art but avoid it when it discomforts them

Sunil Awachar unpacks the politics of art in the larger vision of casteless society.

- Vishal Thakare

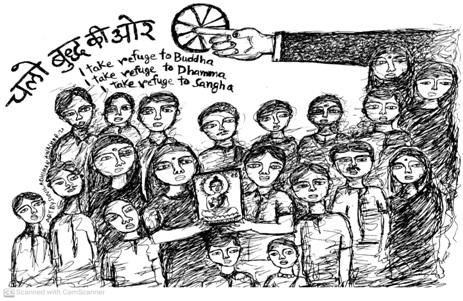

“Shaking the Oppressive Brahmanic is the Expression of My Art and People Sharing the Vision of Destabilizing these Structures are My Gallery”, says Sunil Awachar, a noted Ambedkarite Artist. Explaining the need and idea of anti-caste art and its aesthetics, Sunil Awachar unpacks the politics of art in the larger vision of casteless society in the light of ever-increasing intolerance and erosion of constitutional values.

Over the past few years, your paintings have received critical attention and wider recognition, particularly its Ambedkarite nature and explicit articulation of issues is something people relate with their everyday life experiences and history. What makes you come up with such an imagination which has peculiar historicity and politics?

The code of Manusmriti has controlled our conscience and imagination and disallowed all the realms of creativity by imposing enslavement. If we want to free ourselves from these rigid oppressive shackles, we have to reject it through various actions. My painting symbolizes that action. It rejects the codes of Manu that denied us education, freedom to walk in public spaces and even to think. My art militates against Manu’s code that dehumanizes human personality and stands for dismantling the institutions that control our conscience and imagination through Brahmanism.

Therefore if we want to cultivate new thoughts that do not take control of our mind, we must express through all possible forms of expression such as writing, painting, pursuing education, dancing, singing and wearing good clothes, etc. Every act such as riding a horse, Dalit women contesting the election and putting on ironed clothes, etc. on part of Dalits which was denied to them by the code of Manu. That announces the call for freedom from Brahminic control of our body and mind. It is important for us to engage in incessant creativity informed by anti-caste philosophy. When I say anti-caste I mean the assertion that is embedded in dismantling and destabilising Brahmanism.

The anti-caste struggle and movement has produced different instruments of resistance in agitating against caste oppression. Besides literary expressions in the form of poetry and autobiographies, the cultural space is also invigorating. It is said that artists are an agent who creates art. After looking at your paintings, it appears simple and speaks a particular socio-political reality. What is your motivation behind capturing it and how is it different than mainstream paintings?

The predominant understanding of Art perceives it to be a commodity that can be consumed for one’s pleasure. For me, art cannot always be a commodity for consumption purpose which can be used to decorate walls of houses or derive pleasure from it. Neither it cannot be separated from society nor be produced in isolation given the complex socio-political realities that we inherit in India. My individual act of painting is not mine; it has a collective memory and wound inflicted on my (Dalit) community which must be despised by every human being. Brahmanism has marked us as inferior beings and interiorised each and every aspect of our life. Right from the food we eat to clothes and the ringtones we play on our mobile phones. It is brutal than the war in many ways. In war, you are crushed or defeated once but in Brahminism, Dalits are crushed every day, their human personality is ripped off under the garb of caste. They do not exist in the eyes of the upper caste.

My art is borne out of this necessity to visiblise Dalits as human beings possessing equal worth as every other human does. It seeks to remind people about the structures that continue to enslave and brutalized us for centuries. It not only registers dissent against it but also aims to cultivate agitation and aesthetics for larger systematic change that will reinstate the collective self which is lost due to the brutal institution of untouchability encoded in the Manusmriti.

The smile on a Dalit’s face I create in my paintings is contextual, it is neither pleasing one like Monalisa’s nor it is completely hopeless. It has aspiration and agitative character. Through my art I want to tell that those are silent and mute about Dalit oppression, they are violent. The veil of ‘conscious’ ignorance and callousness they practice towards Dalit’s cause is their cruelty and cessation of humanity among them.

In your paintings, you capture the everyday humiliation of Dalits by creating powerful symbolism and spectacles. In one of your paintings, you compare scavenging workers through Gandhi’s spectacle and Dr. Ambedkar’s one. Why do you think it is necessary to look at these realities through these spectacles, and how is it different from mainstream painting works?

I think mainstream painting has stagnated or lost its dynamic and autonomous character by subsuming itself into the ruling power discourse. In other words, it has aided in reproducing structures of inequalities than overturning it. It has not been able to capture the collective of such a brutal humiliation that a Dalit community face. It has become self-loathing and caters to a narrow section of society. It does not capture the realities of the marginalised. Mainstream symbolism by default submits itself to structures that maintain or reproduce the existing power relations and not challenge them.

I think an artist should not be disconnected from the realities of the oppressed, they must hear, see and share their pain as a person living in society. S/he must be able to capture injustice and be sensitive enough to stand for it. The Brahmanical mirror reminds us of our inferiority every moment and continues to define us the way it wants. As an artist, I am deeply infuriated and cannot allow Brahmanism to define me. I cannot be a dumb spectator like other artists from the privileged social location in a time marked by injustice on my community; rather I would like to be a participant by capturing their deep resentment and struggle in my artwork.

I find this way as Ambedkarite way of articulating politics in which art becomes a powerful medium of communication. I see this necessary to assert and distinguish our politics clearly particularly when there are constant efforts being made to trap us in the Brahminical codes and arrest our emancipatory imagination on a day-to-day basis. I believe that my community cannot attain liberation through Brahminic methods and therefore I try to cultivate the aesthetics that defy Brahmanic does. In this process, Ambedkarite symbolism such as Dr. Ambedkar’s spectacles, tie, coat, statues, constitution, power of education, etc. becomes a default language of my art to cultivate aesthetics that is human and universal. In my paintings, I show the revolutionary character of anti-caste methods—Educate-Agitate-Organize which seeks to fully free enslaved mind.

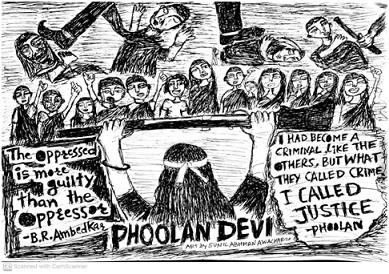

In your paintings, women are assertive; particularly the Phoolan Devi painting was widely shared and related by women across different sections. What do you want to convey through such images?

You need to cultivate your own epistemology in order to dismiss the epistemology of your oppressor. We should not fall in the trap of viewing our emancipation through the routes of the oppressor. The oppressor may offer you temporary concessions of freedom but it is not interested in freeing you permanently. The Dalit woman in my paintings are not subservient; she is rebellious in nature and more informed about the power structure around her. The Brahmanical Patriarchy has rendered her invisible. The recent instance of Hathras has shown that how her body is defaced and deformed by the Brahmanical patriarchy every day.

I see beauty in rejecting the humiliation and challenge the structures that arrest your realms of imagination so powerfully that it is very difficult to escape from it. I make efforts to cultivate hope in my art and writings. Phoolan Devi reminds us of that epistemological route in which women found ways of liberating themselves. This is not to suggest taking weapons but to defy the structures that define and control you.

The canvass in its current form is increasingly becoming digitalized and accessible; it has transgressed the traditional boundaries of exhibition spaces such as galleries. Your paintings have received greater attention on digitalized space and found their audience. How do you see this digitalized space?

People who are at the receiving end of oppression and stand for the anti-caste movement relate with my art and find their agency and politics in it. They often convey their solidarity through re-posting it, putting it on WhatsApp, Instagram, Facebook and other social media platforms. I think this digitalized place has provided us the autonomy to create our own space and own galleries.

The mainstream galleries have never given space to Dalit art or art that destabilizes Brahmanism. But it has carved out its galleries and space amidst all sort of crisis. I think people who share the vision of destabilizing these structures are my gallery which is open and boundless and do not confine within the Walls. This boundless and address less gallery acts as activists charged with anti-caste aesthetics to annihilate the caste and institutions that perpetuate oppression.

But we need to be cautious about algorithms, as many instances have shown sometimes it can be blind to some socially sensitive realities like caste and race. We need to make it inclusive and discursive grounded insensitivities of social realities.

How do people react to your art?

When I painted an armed Phoolan Devi alongside a crushed woman, hundreds of women related with it and shared it widely. This shows deep-seated anguish among women against the systematic subordination and perpetual violence inflicted on them. It also tells us about the absence of art that captures their agency and the conceptual world and offer them some comfort. By endorsing Phoolan Devi I painted, I think they wish to see armed Phoolan as a necessity of today’s repressive conditions which fail to recognize them as equally worthy and dignified individuals.

I also receive threats from some disgruntled minds. When I painted alternative imagination of Ramayana depicting Periyar, I was threatened by some right-wing person. Some complain that my art doesn’t please them, I tell them it is not an item song performed with the intention to please people. Some see it complaining and advise me to paint a “positive” picture.

It seems you are very conscious about the color you chose in your art, is there color politics involved in it?

I largely use Blue and Black in my paintings. The scheme of color and lines represents anti-caste politics articulated through Ambedkarism. Black is considered inferior and bad in our society, and there are various abuses and slangs around it. But I see Black colour as a sign of resistance and want to destabilize the dominant perception by showing Black as powerful and beautiful too. I want to unsettle the binary between white and black and humanize it by making people informed through my art.

Where your art do finds its space when it comes to traditional gallery exhibitions?

My work does not find its space in mainstream galleries and not necessarily qualify as salable art. There have been shifts in painting and its subjects over time. Some artists like KK Hebbar and MF Hussain made an attempt to transform Indian painting discourse and made women's oppression focus of their paintings. Both expressions found their audience. But I did not find Dalit struggle such as atrocities, Dalit women being raped and paraded naked, etc. acquiring space on canvas and becoming part of the mainstream. Even if it found its space it lacked the authenticity of experience and therefore missed on the spectacle—Ambedkarite epistemology.

Perhaps it was the first time in Maharashtra when renowned Dalit writer and intellectual Gangadhar Pantavane, who used to publish an acclaimed magazine called ‘Asmitadarshan’, asked me a painting from Dalit perspective. It was the Asmitadarshan that published my painting first time.

Are there any other painters who share a similar vision like you?

Yes, there are artists like SV Savarkar, Sridhar Ambhore and BM Padsawale some of the people who have produced reflective work that falls within the anti-caste art. And the young generation is really doing a revolutionary job.

But some of our artists have a sense of insecurity of being left out or boycotted if they expose Brahaminism through their art. Some are reluctant in questioning the system in their art. I think Dalit artists cannot produce their art by sitting at home, S/he will have to become an active participant in their agitation and protest with their art becoming a fuel of it.

How do you mobilize resources such as canvas, colour, etc.?

Frankly speaking, I could get proper access to canvas and colour at the age of 40. There are barely any financial returns of my art as it hardly qualifies as a salable commodity in the market of art goods. I think my painting is not for sale rather it is an instrument of bringing social change. You cannot reduce it to a commodity. Like Picasso had paintings called Guernica- as anti-war paintings, my paintings are anti-caste who does not necessarily follow exact measurement and form like Picasso’s but it has clear politics. But there are huge social returns to my art, even if Dalit woman residing far away in Bihar saw my painting on a mobile phone and develop a sense of assertion, I would value it than traditional ways of selling art.

How do you see the future of Dalit Art?

As I told you earlier, people often intend to seek pleasant experiences from the consumption of art and derive satisfaction from it. If it discomforts them they may averse or dislike it. My work unfolds the faultlines in our societal structures and discomforts those who benefit from the system. They see my expression as pessimistic and problematic and hostile to their beliefs. They often ask me how long I will paint such depressing and painful paintings. I respond to them until and unless the structures of oppression are intact, my brush and pen will revolt against it untiringly and uncompromisingly till its removal. I see a new aesthetics being cultivated by Dalits and believe that Dalit art will rise as a most humanizing art and heal the community from historical hurt to arrive at a beautiful aesthetic experience that not only give them a sense of ownership but also free them from all sorts’ of infirmities imposed on them.

Vaibhav Thakare is a freelance academic based in Mumbai and has graduated from TISS and Berlin School of Economics and was teaching at Centre for Labour Studies, TISS as visiting faculty.